WoN Platform Expansion Plans

A resilient architecture is flexible enough to expand as limitations are reached and to adapt as new requirements surface. This page explores the ways in which the World of Nuclear architure could support orders of magnitude more traffic, as well as additional popular features.

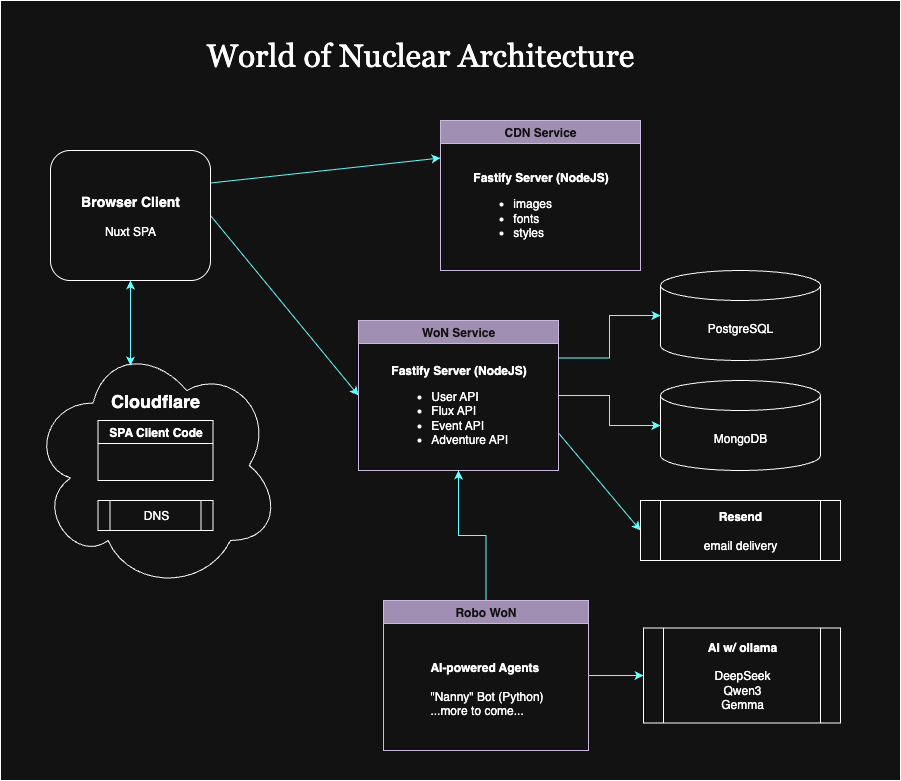

For reference, this is our current baseline architecture

Scalability

We can think about "what if" scenarios involing scale. Let's tackle the three most likely areas:

- Traffic: handling sudden spikes and order-of-magnitude increases in baseline engagement

- AI automation: bringing more agents online to interact with users and support operations

- Simulations (future feature): generating, storing and presenting "real-time" volumes of system data

Traffic - Human Usage

Utilization as of 2025-7-23

- 1,500 unique visitors over the last 7 days

- 285 visitors over the last 24 hours

- 187 MB served

In plain language, this site gets negligible traffic. That is to be expected given the fact that we are building out in the open. In other words, while the site is publicly available, it lacks the features that lead to heavy usage and explosive growth.

Also, we have yet to begin serious marketing. What traffic we have is thanks to people who follow us on X and bots.

So what happens when we start to become popular?

Client Code & CDN

Our client code is hosted on Cloudflare, which is designed for massive scale and global availability. We may hit our limits on the free tier, forcing us into a paid subscription. That would be a happy problem, easily solved.

Micro-services

The primary micro-service, "WoN Service," is hosted on a virtual machine at a Hetzner data center. One host is running Nginx, Fastify, and Postgres for production and staging.

Information about the CPU load, memory utilization, and disk space is readily available. Setting up notifications and alarms for nearing operating thresholds would be trivial.

The shared VM is at the low end to contain costs without hitting operational limits. This has been fine while most of the real (i.e., non-bot) traffic is from the Development Team. That also means we could handle a couple of orders of magnitude more load by simply getting a bigger, dedicated machine.

Beyond that, we would need to evolve our strategy.

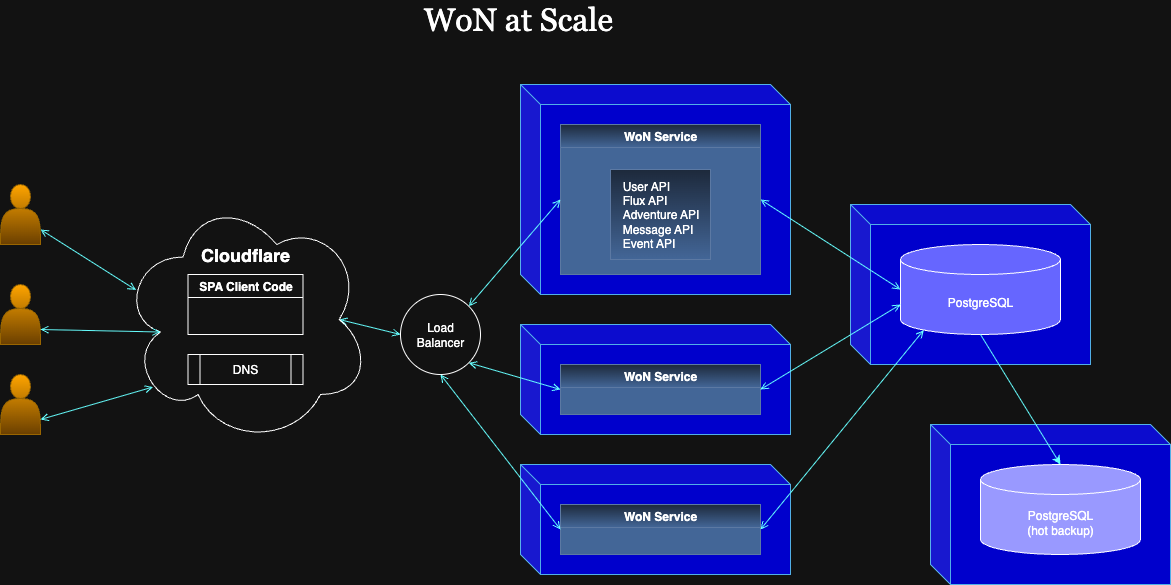

The next mitigation step would be to separate concerns, which would also result in a more robust and resilient solution. Robust in that it would handle load more gracefully. Resilient in that minor issues would not bring everything down.

Hosting Postgres on the same machine as the service is great for low latency (as low as possible). However, we can relocate Postgres to a dedicated machine within the same subnet with little noticable difference in speed. Hetzner provides subnets that group VMs in the same data center. That separation would allow us to scale the services and database independently, where each will have its own performance profile.

While we are at it, we might consider running a hot database backup on a third VM. This would be for failover in the event of a problem with the main Postgres instance. Being able to switch over would enable no-downtime upgrades as well.

In addition, we could also take snapshots from the backup, keeping this activity off of the machine that is servicing client requests. Depending on the backup latency, we might only put the last few minutes of updates at risk of loss, which would be tolarable for most of our use cases.

Eventually, when we max out the size of database host, or reach a tipping point in the economics of scaling, we could host read-only instances of the database to offload jobs that are focused on anaylsis and other high-join activity. The main instance would be favored for change activity.

Alternatively, we can consider splitting the main service into multiple services based on utilization patterns. That would lead to separate databases for each concern. One system for user information, perhaps another for activity logs, Flux might get its own, and so on. Each split incurs management overhead, but we would only need to level up once and apply the new pattern to each micro-service.

In the last month, we have begun to use MongoDB as the datastore for our Adventure Game. Since we are in development, our hosted Atlas instance is sufficient. However, eventually we might need to follow a similar mitigation strategy as with Postgres. First, we can host Mongo ourselves for control and cost containment. Second, we can use containers to configure and deploy multiple instances, assuming we have enough traffic to merit a massive scale out.

Finally, let's return to the services. When we need to host more than one, it makes sense to deploy containers that hold the latest production code. That would give us a consistency over what is deployed and an easy way to scale up instances. Those instances would run behind a firewall (provided by Hetzner).

Let's draw a diagram that includes deployment and extra instances of components.

If you have a sharp memory, you might be wondering about Resend for email delivery? That is another fully scalable service that we are leveraging for free. If we had more registrations and other email-triggering events, we might need to start paying for volume of delivery. There is little chance, short of some kind of service attack, of exceeding the limits of the Resend service.

Handling AI Activity

When you read any news about AI, you would think that using AI will cause global blackouts from the power drain. However, that is more to do with training AI models than with using them for inference or generating clever responses for curious users.

Here at the World of Nuclear, we see little reason to train our own models. At most, we might want to supplement the general models the world is providing. Especially if they need better details about nuclear-related topics. That training can be done on separate infrustructure.

For example, if we want to add a RAG pipeline to load nuclear power plant specs, we could stand up a Python service that connects to Mongo for data ingest, chunking, embedding, and FAISS indexing. Assuming we have an AI-enabled chat bot, that information would be incorporated into responses when relevant.

Still, even generating responses takes a fair amount of compute, enough to compete with other processes on the same host. This would merit spending some money on a few specialized machines. We might want to rent GPUs for that if demand is high enough. And we probably need to attach SSD or NVMe drives for additional fast storage capacity. Aside from that, the hardware systems should scale up the same way we scale our microservices.

When we need concurrent processing, we might want to introduce a code-based dispatcher to place work on a queue, and have worker nodes take work as they become available.

Supporting Simulations

Imagine we are running full-scale simulations of nuclear power plants. Imagine that hundreds of users are running their own.

The hardware to run a simulation would look a lot like the hardware to run microservices. Essentially, there would be some number of Python, Go or Rust processes gathering data from (simulated) "sensors," running that data through physics models, and capturing events as time-series data sets.